The Prisoner’s Dilemma – cooperation versus conflict

Dear all,

It’s World Pi Day(!) so to celebrate we’ve enjoyed a week of Maths Enrichment in school, starting on Monday with an exploration of the Prisoner’s Dilemma, developed by mathematicians in the 1950s and since used to observe, predict, and inform human interactions in many different scenarios.

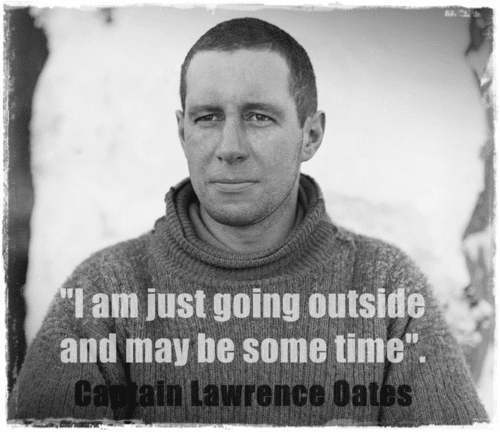

The early stages of the Cold War saw rivalry, hostility, and indirect conflict across many different fields including space exploration, proxy wars, and a nuclear arms race that on at least one occasion, if not more, brought the world to the brink of destruction.

In the US, an organisation called the RAND Corporation was established to strategise all these areas, including predicting how their Russian counterparts would act. Their work on predicting the Soviet Union’s likely strategy for producing nuclear weapons and therefore recommending what America should do to counteract it involved considering the issues of cooperation and conflict. It was developed by another mathematician, Albert W. Tucker, who named the approach The Prisoner’s Dilemma.

If you haven’t come across it before, imagine two people – John and Jane – who’ve been charged with committing a serious crime together. Both are kept in separate cells and offered a deal: John is told that if he confesses and Jane stays silent, he will go free and Jane will get 5 years in prison; if he stays silent and Jane confesses, she will go free and he will get 5 years in prison; if they both confess they’ll each get three years in prison; and, because of a lack of concrete evidence, if both stay silent they will each get 1 year in prison.

Jane is told the same. Both have to make their decision before they know what the other person has decided.

The Prisoner’s dilemma illustrates a clash between individual and collective interest. Where this dilemma is a one-off, most people choose to confess even though it means they will go to prison (because despite the fact they will go to prison for either three years or one year, they won’t get the worst outcome – five years in jail). This is the Nash equilibrium – named after the mathematician John Nash – being the safest choice for each person even if it’s not the best overall outcome.

On the other hand, if John and Jane faced the same dilemma every day, over and over again, they would start to notice patterns – if John confessed yesterday, Jane is likely to do so today, but if John stayed silent yesterday, Jane may do so today. And so on. In the repeated Prisoner’s Dilemma, we tend to change our behaviour because we think more about the long-term effects of our choices. In this version of the dilemma, cooperation often emerges because players realise that acting selfishly will be punished later.

One of the most successful ways to play the repeated Prisoner’s Dilemma is the Tit-for-Tat strategy. This advises that players start by cooperating – in the Prisoners’ Dilemma by staying silent and trusting that the other person will do the same. After that, the advice is to do what your opponent does – if they betray you, you betray them in the next round, but if they cooperate you do the same. In this way, cooperation is the starting point, further cooperation is rewarded, betrayal is punished and forgiveness is built into the model because as soon as your opponent cooperates with you, you reciprocate with them.

Many readers will know that the Prisoner’s Dilemma is part of Game Theory which, as well as being a fascinating intellectual exercise, is also something used in real-world applications. In Monday’s assembly, we reflected on the importance of trust – when people trust each other, they’re more likely to cooperate. It shows the impact of long-term thinking – in life, we often interact with the same people over and over, and with classmates, teammates, friends, and family members, thinking long-term helps us see the value of being cooperative. On the other hand, selfish choices may bring quick rewards but they can damage relationships in the long term. It also shows the importance of reputation: as shown in the repeated dilemma, our actions build a reputation. If we’re known as someone who cheats or acts selfishly, people will be less likely to work with us, whereas if we’re known for being reliable and fair, others will trust us. Finally, everyone makes mistakes – we let people down sometimes, we make errors of judgement and the same is true of others. The tit-for-tat strategy, which forgives occasional betrayals, shows how forgiveness can repair relationships.

In summary, the Prisoner’s Dilemma shows us both the reasons why conflict happens – mistrust, greed, and short-term thinking – and how we can enhance cooperation through building trust, thinking long-term, and having fair systems that reward good behaviour and discourage cheating.

Have a good weekend

Best wishes

Michael Bond